The Grove neighborhood of St. Louis, named for its original function in the 1800s as a spacious and productive walnut grove, is coming back to life thanks to innovative partnerships between commercial and residential entities, according to speakers at a recent program of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

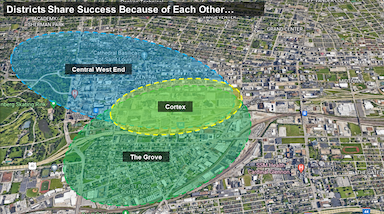

The Grove represents "both what St. Louis is and isn't," said Matt Sutherland, an architect with the planning, architecture and design firm JEMA and with AIA-STL, in introducing the speakers. The area started as Ward 17 and encompasses the Washington University Medical Center, Cortex, and St. Louis University and its hospital.

The varied projects underway in the Grove represent "the human experience," according to Abdul Abdullah, executive director of Park Central Development, a 50(c)3 Community Development Corporation (CDC) that "works to strengthen and attract investment that creates and maintains equitable vibrant urban neighborhoods and commercial districts where people want to live, work and play." It was originally three CDCs that came together to create Park Central.

The organization carries out its mission through neighborhood planning and services; infrastructure projects and improvements; administering commercial, business and special taxing districts; and providing technical assistance to encourage investment in the community, Abdullah said. In a city with "a weak mayor structure, Park Central acts as the local city manager on the neighborhood level to ensure that proper services and coordination [occur]."

For the Grove, that has meant a transformation to an area that declined from a population of 14,000-plus in 1950 to about 4,000 in 1990; 3,700 in 2000; and 2,900 in 2010 to a comeback at 3,458 in 2020 and growing. The LGBTQ Attitudes Night Club in 1988 and iconic signs installed in 2010 to create "placemaking and branding" are considered catalysts in the revitalization process, Abdullah said.

Abdullah listed successes as contacting and serving more than 66,000 residents annually; more than 500 hours of community engagement and technical service, including 400 hours north of Delmar; more than $1 million in direct anti-displacement to residents; creating and securing more than $1 million in public and private dollars for the City of St. Louis Real Estate Tax Assistance Fund and saving 68 homes from tax foreclosure by the city; facilitating and project-managing more than $1 million in infrastructure projects; managing commercial districts that generated more than $200 million in sales; providing technical assistance and support to 320 businesses and more than $200,000 in direct grants or assistance to 40 businesses, 89% of which were minority- or women-owned; and facilitating more than $250 million in new development.

Stabilization programs have included Real Estate Tax Assistance and a Small Business Grant & Technical Assistance Program, he said. To head off the displacement of residents by new growth and commercial activity, Park Central ensured that 51% of new housing units are affordable and 49% are at market rate.

"If you want to do a development, we have the resources," Abdullah said. "We help with the process." He noted that anyone wishing to do a development in the neighborhood is expected to include a way to ensure that residents are not displaced by construction or gentrification.

For Abdullah, "the big question is how do we get here — how do we help people? The first way is responsible leadership and integrity in the process, allowing people to work together." He credited the late William Danforth, chancellor of Washington University, for laying the groundwork as "the anchor of the region" for committing to keeping the medical center in the city, and former 17th Ward Alderman Joseph Roddy, for "sharing power and decision-making."

Cortex and both public and private institutions have been key to the revitalization process, he said.

"Cities are like people," Abdullah said: "They grow, they die and they're reborn."

For John Mueller, AIA, LEED AP, NCARB, managing partner at JEMA, the Grove is "kind of a hidden treasure." Changes in the area can be viewed through 30 years of being an architect, traveling to Scandinavia and studying psychology. JEMA recently finished Union at the Grove for Greenstreet: six buildings that represent innovation in design that drew on those sources.

New developments over the past 20 years have included Rockwell, the Swan multifamily development, Union at the Grove, Washington University office space and more. These and other projects reflect a partnership between Park Central, the Wash U Medical Center Development Corp., Greenstreet and JEMA.

A big part of "what's next," Mueller said, is housing. "Urban development is hard to do right," he noted, citing research that has said more is known about what makes good habitats for animals than for people.

Commercial real estate professionals should keep in mind that scale is vital in revitalizing a community, Mueller noted. "There is a misconception about perception. When we see a building, we quickly transfer what we see to a feeling. When we look at cities, the concept of 'holding' is important to understand the proper scale. Spaces that hold us feel right, make us feel good... Part of scale relates to closeness, especially as it relates to walking down the street."

That concept was in mind for projects like Union at the Grove, where projects did not include retail. One technique was to place entrances on the corners to "mimic corner stores, creating a retail look along the street," Mueller said.

"We could have gone with a big building, but we felt that six smaller buildings would have a better impact," he said. "The intersections between multiple buildings (enhance) interaction (among people). It's similar to a forest versus one tree."

Union at the Grove also features a diversity of architecture even though "it would have been a lot easier to make all six buildings look the same." A key to the area's new lease on life is "the new and old existing together."

Architectural diversity can be an important factor in fighting gentrification, Mueller noted. "The new and the old living together is a great dynamic."

Even with commercial projects, "it's important that we remember we are all here for people — everything we do is for people," said Tim Gaidis, LEED AP, BD+C, principal and project designer with the design, architecture, engineering, and urban planning firm HOK, in discussing the Cortex Innovation Community as "a great success story" that has combined technical elements with that essential focus.

Cortex, the acronym for the Center of Research Technology and Entrepreneurial Exchange, has had a huge impact on the revitalization of the Grove, Gaidis said. To date, HOK has completed five core/shell buildings and more than two dozen fit-outs, with two more fit-outs in design and two more to come. A Cortex Commons is being created as "a sort of hearth; a partnership in design thinking." There are 25 tenants in place and ongoing test fitting and updates.

"Stuff is spawning out of Cortex," Gaidis said — including Ikea and even extending outside the Grove to artistic makers' spaces on Delmar.

Cortex reflects a "desire to have variety in the types of buildings, both something organic and in terms of growth. Even though HOK designed all five buildings, they look as though each could be from a different source," he said.

The complex also reflects its developers’ idea for stopping the "brain drain" in St. Louis and keeping intellectual capital from leaving.

Cortex had an area of post-industrial buildings, many of them empty, on a 200-acre site. The area now features "lots of co-working space, which is very important for small companies and startups that can't afford to lease space but can afford a membership ... The idea is a network of innovation spaces — no cul de sacs or dead spaces ... continuous spaces."

The complex includes a former St. Louis Post-Dispatch printing plant now functioning as a workspace and the Aloft Hotel and Wasabi restaurant. Future adaptive reuse plans include making use of a grain elevator on the property rather than tearing it down, along with workforce residential, Gaidis said.

Gaidis cited risks of revitalization as the challenges of an "unchecked growth model," because excessive growth can throw some uses out of balance; the "cost to play," such as leases, parking and providing services as a community improves and becomes increasingly popular; reducing gentrification by keeping housing costs accessible for "diverse and desirable groups"; and heading off the "location shell game," such as when St. Louis entertainment districts launched with fanfare but didn't survive.

The next focus is on "the future of our 'good neighborhood,'" he said. "These districts share success because of each other; all that makes them more robust. The question is what is too much — when do we know when to stop? We have to work on holding the sweet spot but still be growing. You can't have all-multiple uses in all areas."

____________________________________________

Feature image courtesy of HOK.